- +65 61000 263

- Contact@COE-Partners.com

- Newsletter

Lean Six Sigma DEFINE Phase

Lean Six Sigma DEFINE Phase

In the Lean Six Sigma DEFINE phase, the foundation of a successful project is laid. The key to success is a project definition that is based on a real business problem and a description of the project objective and the people needed to solve the problem. Since each process serves one purpose – fulfilling the requirements of the process customer – the voice of the customer (VOC) will be collected and translated into measurable specifications. Additionally, a high-level overview of the process will be mapped in order to align the understanding about the scope of the process and its steps among all members of the project team.

The principal objective of the DEFINE phase is to establish a well thought-through project charter. The Lean Six Sigma DEFINE phase helps to “organise success”.

The following list of tasks may not be needed for all Lean Six Sigma projects, on the one hand. On the other hand, some projects may even require additional tasks to be completed. The list of tasks required depends on the problem that needs to be solved and the data that needs to be handled.

1. Define the Problem and Charter the Project

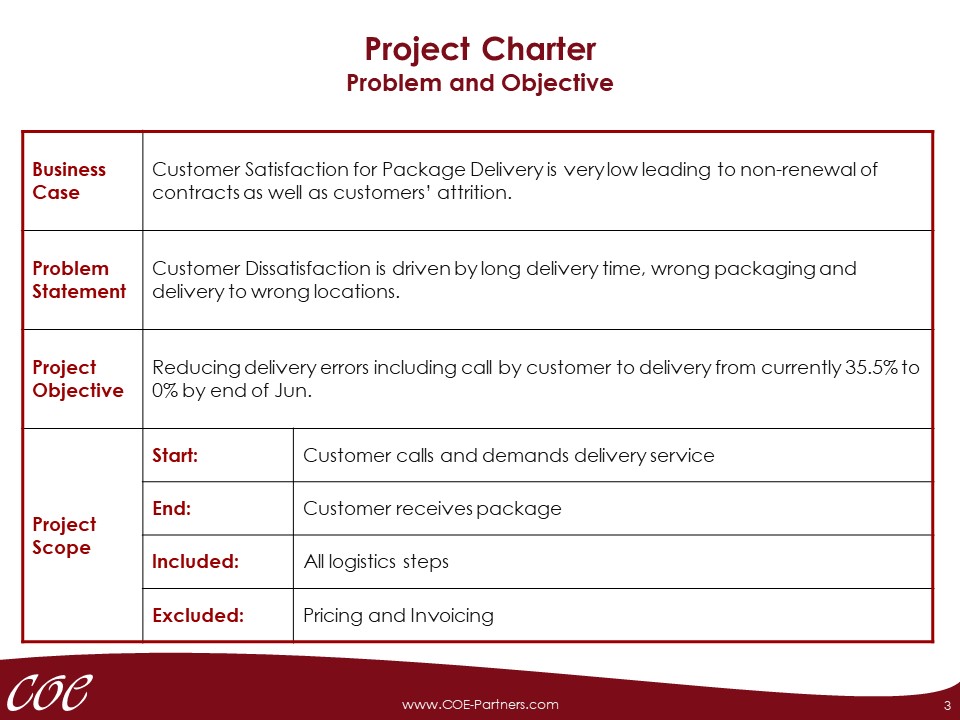

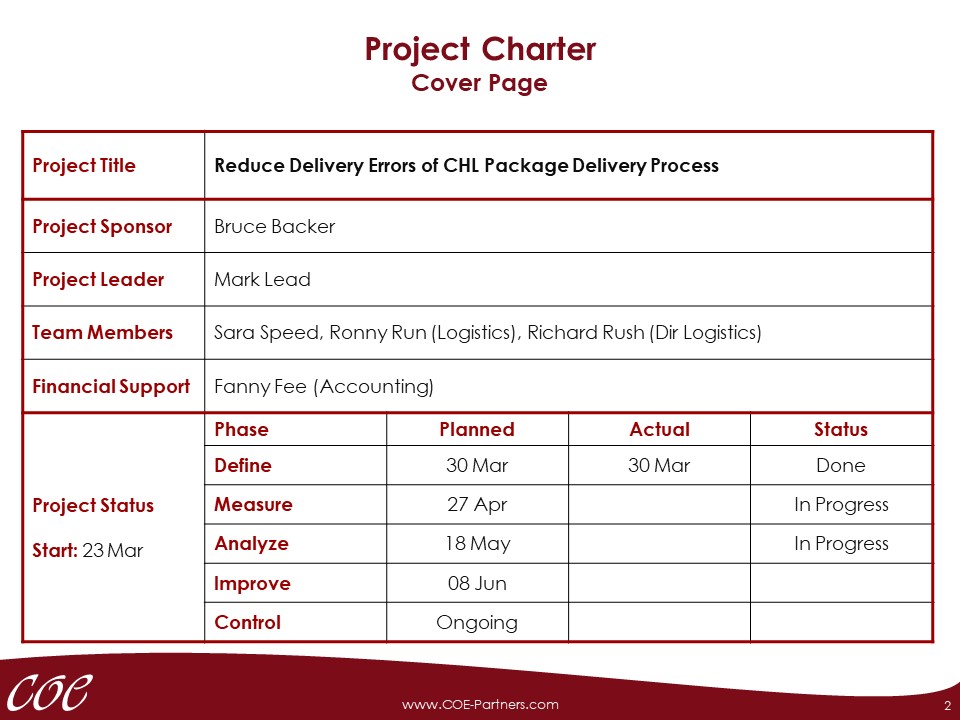

The project charter contains a summary of all information relevant to the start of the new project. The objective of the project charter is to elaborate the situation and to describe the scope for the project. A comprehensive project definition includes business case, problem statement, team composition, project milestones and project objectives.

To ensure the success of the project, it is essential to gain buy-in from the organisation.

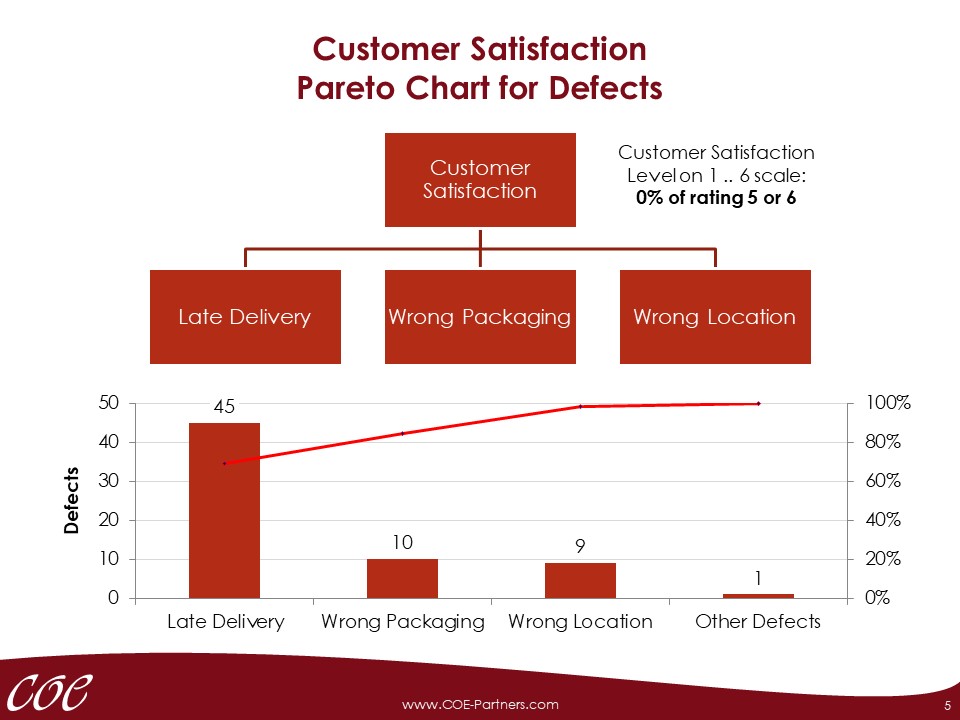

The importance of the project can be derived from financial indicators like losses or reduction in revenue due to the problem that is supposed to be eliminated. Additionally, customer or employee feedback can be used as trigger for working on this project (Figure 1).

All above mentioned situations are much more impactful if they are shown in a graphical way. These graphs should display both, the extend of the problem with its impact and the target that the project is supposed to achieve. Pareto or pie charts and even bar charts are well suited to show the contribution of the problem to the business case. If the problem situation has been developing over time, a time series chart might be able to show the growth of the problem.

All these charts should be easy to understand and able to serve as basis for decision making by the management team. Graphical displays of details like defect categories or claim categories are less suitable for this purpose than graphs showing the impact like additional costs, loss in capacity, customer attrition or employee turnover. A link to the strategy of the organisation is a powerful way to support management decisions. At the same time, it serves as a purpose for employees to support the project.

Problem Statement

While the business case shows an organisational perspective, the problem statement is strictly process related. There are two fundamental groups of problems:

- Turn-around-time related problems and

- Defect related problems.

Even though both groups are usually interrelated – i.e. long turn-around-time is often the result of defects in process or supplies – it is beneficial for managing the project to know and describe the fundamental characteristic of the problem together with its apparent metrics.

Target – Specification

Metrics are consequentially turn-around-time or defects. Turn-around-time as well as defects should be displayed as a percentage of fulfilment of a specification (target). This means, the specification for a turn-around-time related problem is a time target. However, the percentage of its achievement serves as metrics. Averages as metrics have to be omitted.

Usually, there is only one metric that describes the problem leading to the business case. In case it appears necessary to use more than one metric to measure the problem, it could be a hint that the project scope is too large. Then the appropriate question to ask is: do these metrics and the underlying problems all need to be tackled in one project or are there multiple problems? The advantage of reducing the project scope lies in reducing the turn-around-time for the project which usually leads to the chance of showing results earlier and hence better buy-in for other projects.

Project Scope

When defining the process under investigation, the knowledge or, at least, the hypothesis about the root causes for the problem plays a key role since problems can only be solved by working on the root causes, not at the place where the symptoms appear.

For example, if packages are delivered to the wrong location, the root cause could be found in the process of delivery or in the design of the directory. Looking only into the process of delivery might not be enough to solve the problem.

Although, neither root cause nor solutions are known in the Lean Six Sigma DEFINE phase, it is often possible to ensure the process that most likely carries the root causes is included in the scope. Having the process stakeholders in the team is an important prerequisite to achieve this. With this knowledge, start and end point of the process can be defined accurately. This determines the horizontal scope of the project.

Due to the patterns of occurrence of the problem, it might be possible to reduce data collection and analysis by defining a vertical scope. This scope determines for example, which products or services or which client groups should be included or excluded.

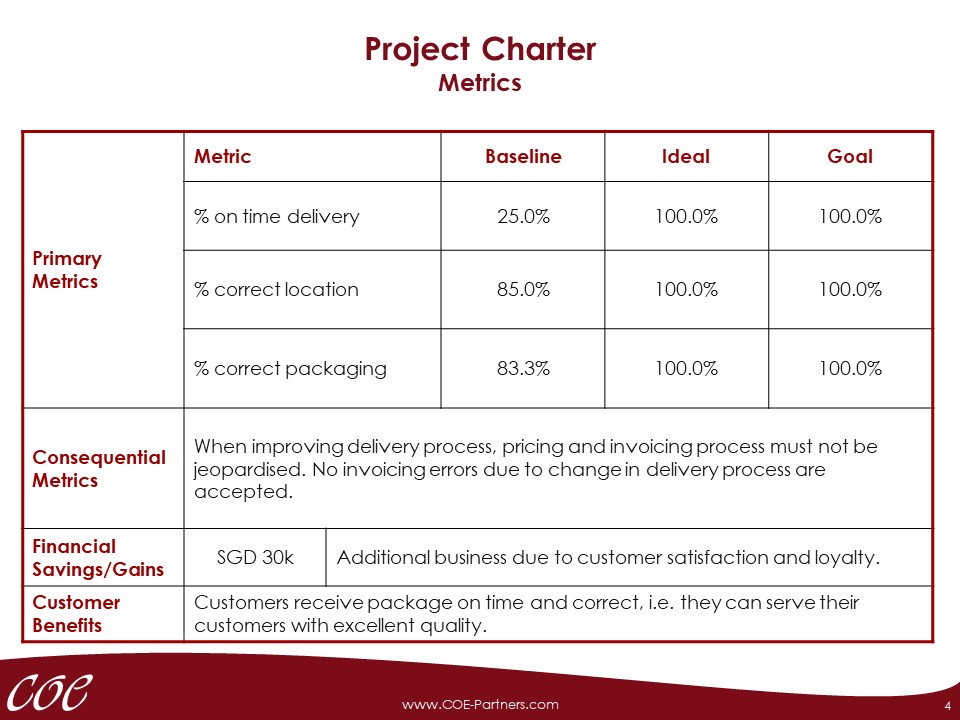

Project Metrics

Whereas in the previous task the organisational objective has been defined, it is now necessary to determine process metrics. This can be one or more. In case there are multiple metrics, the question should be asked whether all of them are to be tackled in the same project.

If multiple metrics have a similar characteristic, for example turn-around-time for a loan application and credit decision time for the same process, similar or the same root causes are to be expected. This means, covering these metrics in the same project makes sense.

If multiple metrics have different characteristics, for example turn-around-time for a loan application and wrong credit decisions, different root causes are to be expected. This means, it might be advisable to work on these problems in different projects.

Often, these metrics are not known or not known to a great detail. In this case, a high-level metric, an organisational metric can be used for the start. For example, customer satisfaction is a high-level indicator that more often than not does not show which part of the product or service delivery the customer is not satisfied with. After collecting the voice of the customer, this indicator should be replaced by more specific metrics. For each metric, baseline, ideal and target should be shown in the project charter.

Baseline is the information about the process performance at the beginning of the project. In order to reduce the influence of seasonal and random variation of the process metrics, it might be necessary to show an average of the last three to six months. This does not work in case of systematic changes on the process during that period. Systematic changes can be driven by man-made process adjustments or can be drastic process issues that change the process performance more than the daily observable random variation. In this case, the average of all data points after that change should be taken as baseline.

Ideal is the best possible performance for metrics. In case of turn-around-time related problems, best possible performance data can often be derived by benchmarking – structured or casual – with best in class competitors, related organisations or even from other units in the own organisation. In case of defect related problems, the ideal should be zero defects. Anything else is a bad compromise. In case of technical processes that have a well-known best in class limit which cannot be surpassed under the current technical knowledge, this limit can be used as ideal.

Ideal is not something we develop ourselves by looking at our own process. The ideal has no practical meaning for the project work. However, it serves as a reference to set the target.

Target is the specification for the metrics. It may be the same as the Ideal. More often than not it is different to the Ideal. The target for the metrics should be derived from the organisation’s objective for this project. I.e. meeting this target should support meeting the overall objective for the project. For example, project objective is often increase of customer satisfaction. However, customer satisfaction cannot serve as target for the project because it is a lagging indicator that will only show success or failure much later. In this case, the project target should be derived after collecting the voice of the customer, identifying the drivers for low satisfaction and mapping the process that leads to low satisfaction. Having done these steps, it is usually possible to determine metrics as well as target for the project.

The target should be challenging. This usually leads to increased support by the management. Additionally, it enforces innovative solutions, i.e. disruptive solutions that are based on “out-of-the-box“ thinking that introduces a paradigm shift. Less challenging targets can be achieved by solutions that are based on conservative thinking “within-the-box”.

In addition to the already defined metrics, it might be beneficial to consider consequential metrics. A consequential metric is not derived from the project objective, but is an often unintended result of working on this project. For example, the reduction of turn-around-time in many processes might increase the risk for process failures. In order to avoid this effect, the consequential metric failure rate has to be monitored at the same time as normal project metrics get observed.

Often it is possible to calculate the potential financial advantage of a project. Based on the business case, the intended process improvement can be translated into a measurable financial benefit. The result is always an estimation that is based on a series of assumptions. These assumptions should be well grounded to ensure acceptance during the management presentation. It is a good practice to check the calculation of the project benefit with the finance department before any important presentation. The financial benefit is a key criterion for project selection.

Increasing the customer satisfaction, loyalty and retention is another main driver for many Lean Six Sigma projects. Therefore, linking project metrics and project target to any customer related metrics is an important task before presenting a project proposal for project selection.

Whereas organisational benefit is a rather short-term indicator, customer related metrics are powerful long-term indicators that show the future of the organisation. Each project proposal needs to consider both perspectives.

Project Team

In order to implement a Lean Six Sigma project, a certain project infrastructure is necessary. This infrastructure includes Lean Six Sigma Council or Quality Council, Project Sponsor, Project Leader, the so called Green Belt or Black Belt, Project Team Members and Project Support (Figure 4).

Whereas the Lean Six Sigma Council does not work on projects but guides and steers the introduction of the methodology as well as the project work, Project Sponsor, Project Leader and Project Team Members are assigned to certain projects.

The Project Sponsor is usually a member of the Lean Six Sigma Council or a member of the middle or upper leadership team. The Sponsor is typically the one who is responsible for the process in focus. It is in his interest to improve this process in order to improve his own KPIs. More often than not, the Sponsor initiates the project.

He typically undergoes a Champion Training of at least two days in order to be prepared for his task. this Champion Training covers at least basics of the DMAIC methodology as well as his role and responsibilities in project selection, project definition and team supervision.

The Project Leader can be a trained Green Belt or a trained Black Belt. Under some circumstances, a Yellow Belt may lead a project, too. Whilst the Green Belt usually has less project experience and is equipped with about two weeks of training, the Black Belt normally has more project experience and has got about four weeks of training. Yellow Belts undergo less training.

The training for Yellow Belt, Green Belt and Black Belt focusses – in different depth and scope – on theory and application of tools that are needed and used during all stages of the DMAIC cycle. For complex projects, it might be advisable to assign multiple Belts as leaders. Whilst a Black Belt takes over the general leadership for the project, multiple Green Belts might be assigned to different parts of the complex process. Project Leaders are not necessarily familiar with the process. However, process experience increases acceptance among Team Members and the chances for success especially for Belt newcomers.

Project Team Members are involved in the project work. It is necessary that each part of the process in focus is represented by at least one permanent Team Member with process knowledge and experience.

Sponsor, Project Leader and the organisation through the ups and downs of the journey. Master Black Belts are experienced not only in leading projects but also in coaching Black Belts, Green Belts and Yellow Belts and therefore are usually rich in knowledge and experience.

In some cases, process customers or/and process suppliers are involved in the project work, permanently or temporarily.

Team Members usually receive one day of introduction into the Lean Six Sigma methodology. Some organisations prefer to train all Team Members with the Green Belt curriculum leading to faster project work and generating more readily available project leaders for future projects.

Additionally, it might be necessary to invite other Team Members at certain phases to the project work. This Project Support might be necessary during project selection and definition in order to let finance staff do the benefit estimation. Additional Project Support might come from IT in order to support data collection during the MEASURE phase.

Especially at the beginning of the introduction of Lean Six Sigma to an organisation, it is inevitable to have an external or internal coach, a Master Black Belt guiding

As for any other project, for a Lean Six Sigma project a project schedule is needed. When planning the tasks, one has to consider that more often than not Lean Six Sigma projects are not full time assignments. Realistically, Project Leaders and Team Members can be expected to spend 10% or less of their time on project work – this is half a day per week. The amount of time necessary depends heavily on the project phase.

An unwritten rule says, that Lean Six Sigma projects have to be completed or at least brought into CONTROL phase within six months. For smaller Yellow Belt projects, two to three months should be sufficient.

The Lean Six Sigma DEFINE phase can be completed in one or a few weeks. Drafting the project charter normally takes only a few days, as mapping the high-level process does. Voice of the customer may need more time if it includes collecting data from customers through surveys, focus groups etc. If this data is readily available, compiling this data and drawing some conclusions are not time-consuming tasks that can be completed in a few days.

Based on experience, the MEASURE phase takes most of the time, because it almost always involves collecting data from the process because available data can usually not be used. If weekly or monthly cycles are expected in the process and shall be revealed through data, then the data need to be collected over multiple weeks or months.

For instance, monthly closures in finance processes and the related reporting generate a certain pattern that not only influences finance processes and staff. In this case, data around some month ends need to be in the data set. Omitting or disregarding this kind of data pattern generates a certain bias that may later mislead data analysis and solution development. In such cases, MEASURE needs to cover multiple weeks.

Although, the ANALYSE phase is the most complex phase in terms of number of tools to be considered and applied, it can usually be completed in a few weeks since most of the work can be done using computer-aided techniques.

For the IMPROVE phase, a similar amount of time should be allowed. In case, this phase requires conducting pilot runs of the improved process, it will require more time. Even though, solutions are never known at the beginning of the project work, for many projects it can be decided whether pilot runs would be needed at IMPROVE.

The CONTROL phase is often not included into the project turn-around-time since monitoring the new process is an ongoing task of the process owner anyway. However, the first part of this monitoring should be done during the CONTROL phase in responsibility of the Project Team in order to ensure sustainable results. After the team has proven capability and stability of the improved process over a reasonable time frame the process is handed over to the process owner. This time frame is often assumed to be three months, but needs to be customised from process to process. Only after successful completion of CONTROL the project can be considered closed.

Apart from the above-mentioned project infrastructure, people who are directly or indirectly involved in the process or effected by changes in the process need to be considered. The so-called Stakeholders need to be listed and analysed regarding their support for the project. Stakeholders are staff members or even external parties with or without management responsibilities who might influence typical project tasks like voice of the customer, data collection or implementation of improvements and therefore are key to the project success. As experience teaches, it is an advantage to systematically organise support for the project by planning appropriate interventions for all stakeholders necessary. Most of these interventions are communication and involvement activities. Therefore, a communication plan should be established summarising necessary interventions.

This communication plan about Lean Six Sigma projects includes activities like

- Information about Lean Six Sigma in organisation’s newsletter or e-news

- Regular updates about the project status at all relevant meetings

- Introduction of project teams during their project work

- Presentation of project results – even after quick wins – at all levels and branches to generate support and prepare roll-out

- Status updates at employee meetings or town-hall meetings

Communication about projects and their objectives should start as early as possible. Although, the support of certain stakeholders is only needed at later project phases, it is advisable to keep them also updated and involved in order to avoid rumours and second hand information. In addition to structured and centrally coordinated communication, the informal communication with some key stakeholders can be a vital part of the project work. Leaders do not like surprises, not even positive ones. They wish to know what is going on. Therefore, the project team has to feed them with information at all stages.

This step has the following deliverables:

- A project charter

- A stakeholder catalogue examining the support of key personnel for the project and measures to mobilise additional resources and backing if necessary.

2. Identify Related Process and Scope

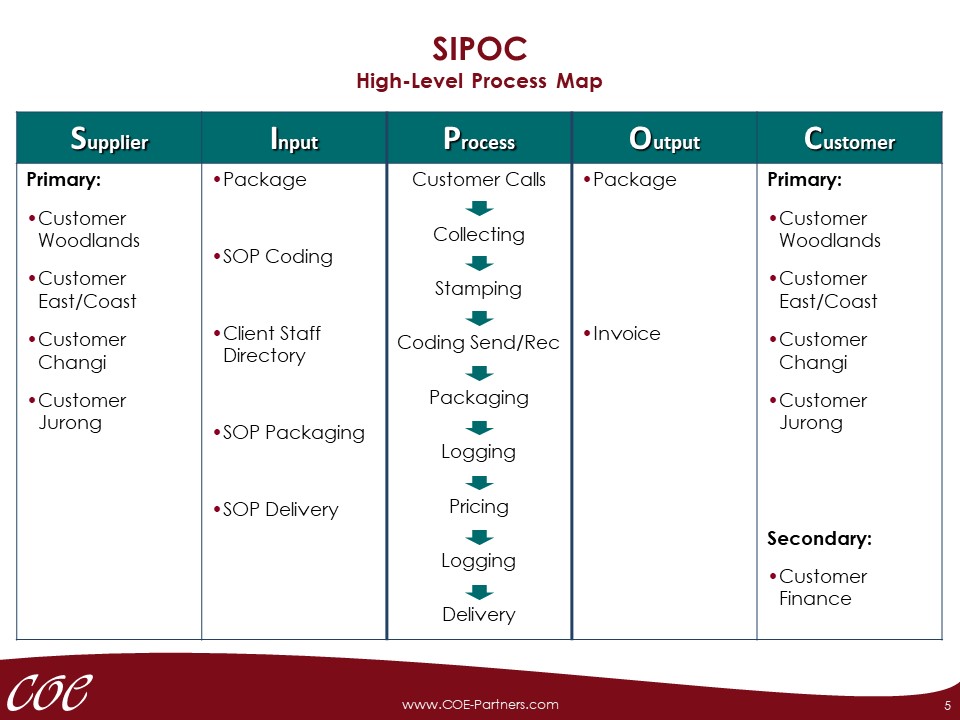

The high-level process map shows process steps (Process) from a helicopter perspective together with process deliverables (Outputs) and their consumers (Customers), process intakes (Inputs) and their vendors (Suppliers). This process map is therefore called SIPOC (Supplier, Input, Process, Output, Customer).

Objective of mapping the SIPOC is to synchronise the perspective of sponsor, team leader and team members on the process. A SIPOC helps to clarify process scope (process start and process end) for the project work. Additionally, it provides clarity about process steps, inputs needed to run these process steps as well as outputs of these steps.

Process start and process end are usually defined in the process scope of the project charter. The process start usually marks the point before the first process step whereas the process end marks the point after the last process step in scope is completed.

The process steps in between have to be listed completely but not in detail. As a rule of thumb, the list of process steps should not exceed ten entries, but can show much less. Usually, the process is mapped in a straight line without decision points and loops assuming that these elements are part of the high-level steps which can be shown in the denomination for those steps.

For instance, the process step “approving application” includes opening of the documents in the IT system, checking of documents for completeness, checking of application form for mistakes, checking of credit report from credit agency. In case of missing information from the credit agency, this information is being requested. The high-level process step approving application is an aggregation of all necessary details that will be listed in a subsequent project task.

The list of process steps needs to include all activities that are within the project scope and necessary to produce the process output unless they are explicitly excluded in the project charter.

Each process exists for the purpose of providing one or more outputs to the process customers. Usually, each process has a main customer – the receiver of the main output – and one or more sub-customers. For the success of the project it is necessary to name all process outputs and all process customers.

For instance, a credit approving process has to deliver a credit decision, an approval or rejection, as main output. The customer for this process step is another internal department that communicates the decision to the customer. In this case, it is of advantage to also name the end-consumer as process customer whose requirements are of high importance for the process. Additionally, other internal departments like Customer Service, Finance and Collections as well as Audit need to receive outputs from this process in order to function properly. They are also customers of this process.

The list of process customers and process outputs must be complete and must not be limited to the problem statement as per project charter.

In order to produce the outputs required by all process customers, the process normally needs a series of inputs. These inputs are provided by process suppliers. These suppliers can be internal departments or external vendors or partners. In service processes, the process customer is often process supplier at the same time.

By way of example, a customer of a loan approval process is a process supplier at the same time because he needs to provide vital information such as bank details, income statement, completed application form, for the process without which the approval cannot be granted.

More often than not, missing or incorrect input from the process supplier leads to delayed or incorrect output to the process customer, who is the same as the supplier. In order to be able to determine requirements for process inputs in a later process step, it is vital to list them completely and correctly in this step.

Note: In service organisations, process customers often deliver critical inputs for the process as process suppliers.

This step has the following deliverables:

- A high-level process map.

3. Determine Process Metrics (CTQs, Ys)

Process customers make the requirements for every process. To know these requirements, the voice of the customer (VOC), and its translation into metrics are key prerequisites for a successful project. Therefore, the objective of this step is to establish a complete list of process customers and their measurable requirements that can be used as indicators for process improvements.

Customer requirements change steadily caused by enhanced offers by competitors or providers of similar services or by environmental changes. Therefore, the assumption that an organisation knows the requirements of their customers is usually wrong and leads to the conclusion that customer requirements need to be collected continuously.

If the SIPOC has been done with a certain level of details, it will show customer segments. Identifying customer segments usually starts with listing primary customers who are often mentioned in the project charter. More often than not, the primary customer is an external customer whose requirements may have triggered the improvement project. In many cases, the process in focus of the project does not serve the external customer directly. The direct customer is an internal department, downstream. Even then, it is advisable to gather customer requirements from external customers.

For instance, Sales is usually in touch with the customer whereas Operations does not have a direct interface with the customer. In case of a project focussing on operations processes only, it is still necessary to collect customer requirements from external customers and target on their fulfilment.

If the project targets on improving the output for multiple customer segments, these customer segments have to be listed in detail together with their specific requirements. By way of example, requirements of loan customers for car loans might be different to requirements of loan customers for computers.

In addition to primary customers, processes typically have secondary customers. These are most likely internal customers who need a process result to satisfy organisational needs like invoicing, book keeping or documentation. These customers and their requirements are not important for the primary customer but they are vital for the functioning of the organisation.

For example, it is not relevant for the customer of a loan, whether the audit department receives a copy of the loan document. For the bank however, this is an indispensable step.

After completing the definition of customer segments, it might be necessary to complete the SIPOC column customer with the newly gained insights.

Requirements for customers listed earlier can be collected in many different ways. The available tools are for either reactive customer data or for proactive customer data. Reactive channels for gathering information about customer requirements include complaints, customer feedback, help desk enquiries, product or service defect numbers etc. Proactive channels include interviews, observations – the so-called Gemba visits, Mystery Shopping and customer surveys.

Reactive Channels for gathering Customer Requirements

Reactive channels are on the one hand very cheap. The information often comes for free. On the other hand, this information is usually quite detailed and often actionable. Therefore, it is key to centralise collection and analysis of all customer requirements that come in over reactive channels. Customer complaints or customer feedback is usually very rich in details because it is given after a customer got in touch with one of our processes during the so-called „Moment of Truth“. Hence, this customer is able to and normally does describe exactly what happened under which circumstances that caused him to raise a complaint or give feedback. Reactive channels deliver useful information about issues that already happened. This information is given by the customer and might be somewhat biased.

Proactive Channels for gathering Customer Requirements

Proactive channels for gathering information about customer requirements are often more cost intensive. It is the nature of proactive channels that customers are surveyed or interviewed without a need from the perspective of the customer. This might lead to reduced interest of the customer in the survey and less care in answering questions. Hence, the quality of information given by surveyed or interviewed customers is lower than information collected via reactive channels. Additionally, the response rate of surveys is usually quite low, because customers do not see a need to participate, consider it a waste of time due to a lack of benefit for them.

Nearly all service providers conduct surveys on a regular basis. The frequency ranges from multiple times per year to once in a few years. In order to receive less biased data, they task market research companies with the data collection and analysis. This approach offers the benefit of benchmarking that is frequently proposed by these companies. However, this way of data collection is very expensive and usually a one-way street. There is often no way to ask follow up questions after completing the survey. Therefore, a combination of multiple tools is the preferred way of gathering customer requirements.

Reactive channels only allow gathering information about existing products and services. Proactive channels do allow, either implicitly or explicitly, testing of new product or service ideas and their acceptance in the market.

Utilising Existing Information about Customer Requirements

Firstly, existing data about customer requirements need to be studied to decide whether they can be used for the project at hand. I.e. does this existing data allow conclusions about customer requirements for the customer segments listed earlier?

Gathering Additional Information about Customer Requirements

Existing data are hardly detailed enough and usually not collected for the purpose of the analysis. Therefore, this data is usually not enough for a successful project. Additional data collection needs to be tailored for industry, customer segment, project scope and other factors that may put requirements on the data to be gathered. Data collection often includes surveys followed by a series of interviews or focus group sessions. If possible, Gemba visits may give additional information about the perception of the product or service in the market.

For end consumers like banking customers, interviews are impractical due to the sheer number of customers and the small sample size offered by interviews. Surveys are more appropriate means to gather data from this type of customer. These surveys can be supported by observations, i.e. Gemba visits. Due to the high throughput of customers through the process, many data points can be collected in relatively short time windows.

For business customers like dealers, focus group interviews are best suited to support data gathered during regular surveys. Business customers are much more likely to willingly spend time for giving feedback that can be used for improving the business since the benefit for them is very apparent.

After collecting data about customer requirements, a huge amount of unstructured customer requirements in different forms might be available that needs to be structured. A relatively easy way for structuring this large amount of data is offered by the affinity diagramme in conjunction with a tree diagramme .

Clustering Customer Feedback

An affinity diagramme helps to categorise large amounts of data. It is preferred if the data to be categorised is of qualitative type. Qualitative data are harder to handle because of the potential ambiguity of this type of data. An affinity diagramme has to be used in a team. Its effectivity is based on knowledge, experience and creativity of team members. At the same time, the affinity diagramme supports team work and helps strengthen the team.

An affinity diagramme of customer requirements is build the following way:

1. Each customer input is written on an index card or a sticky note.

2. Together, team members add note by note whilst trying to group them by topic or theme, i.e. related notes are grouped together so that multiple clusters are created. In order to speed up this process and avoid long-lasting disputes about relationships between notes, this step can be done quietly, i.e. without talking. If team members cannot agree on a category for one or more notes, they may be added to multiple clusters.

3. At the end, clusters receive headlines, i.e. with topic names that represent all or most of the notes in this cluster.

When creating an affinity diagramme it is not necessary to have a similar number of notes in each group. It might be that some groups carry only a few or only one note. The number of notes in the group can be seen as an indicator for the weight of this cluster.

After completing the affinity diagramme, the groups of customer requirements are structured and translated into process indicators. I.e. it is necessary to identify process indicators that are able to represent these customer requirements.

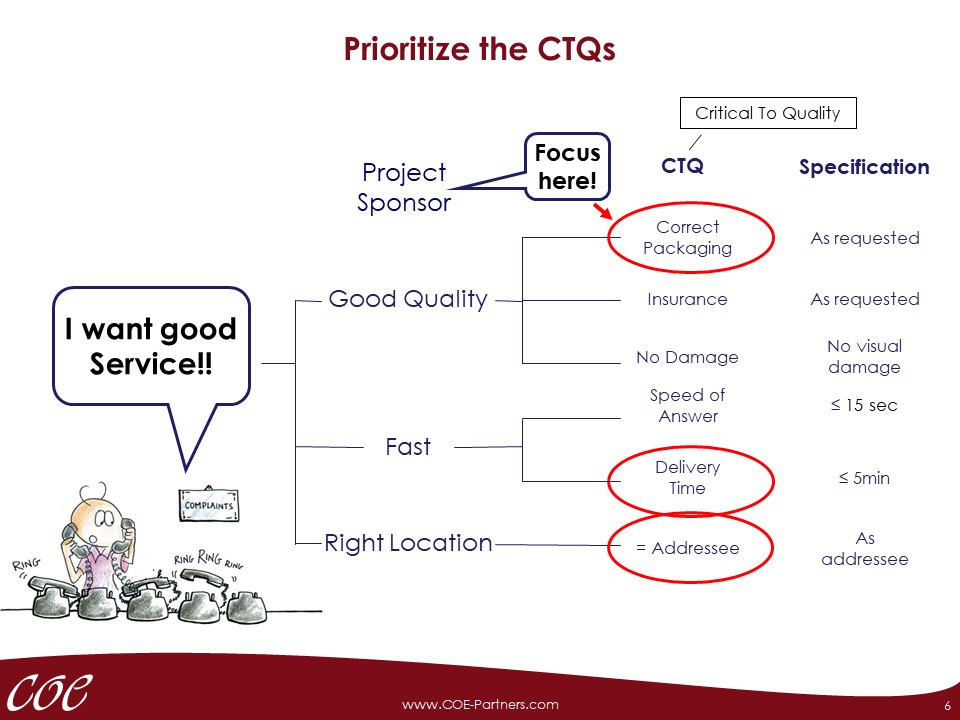

Showing CTQ Tree

A tree diagramme or CTQ tree (critical to quality tree) is used to break down customer requirements as far as necessary to be able to attach process indicators that represent all aspects of the customer needs. This step is vital since customer requirements are usually put across in the voice of the customer that is not specific enough for process improvement, and not measurable.

For example, a customer requirement “I want good service” represents a typical customer statement. However, it does not say what the customer means by that and it is therefore not measurable.

A CTQ tree diagramme of customer requirements is build the following way:

1. Each group in the affinity diagramme represents a branch in the tree diagramme. In our example “good quality” is one of these branches. It is not possible to measure degree of meeting this requirement because it is not specific enough.

2. For each group, drivers need to be identified out of the cluster in the affinity diagramme. These drivers are also put in the voice of the customer. They are shown to the right of the main branch. In our example, “correct packaging”, “insurance coverage” and “no damages” are identified supporting this branch. These statements are subjective as well.

3. Out of these drivers, another level of sub-drivers can be established. In our example, the next step is to derive measurable process indicators, critical to quality (CTQ ), for the drivers. For example, “correct packaging” translates into “as requested in SOP”.

4. In another step, the targets for these indicators need to be set. They can come from benchmarking studies, from customer feedback or from internal decisions based on the experience with this process.

The tree diagramme is completed after all drivers have measurable indicators attached. For business to business customers, the completion of this step can be verified through a focus group session with some key customers of this process. For end consumers, this is usually not possible.

Prioritising Customer Requirements

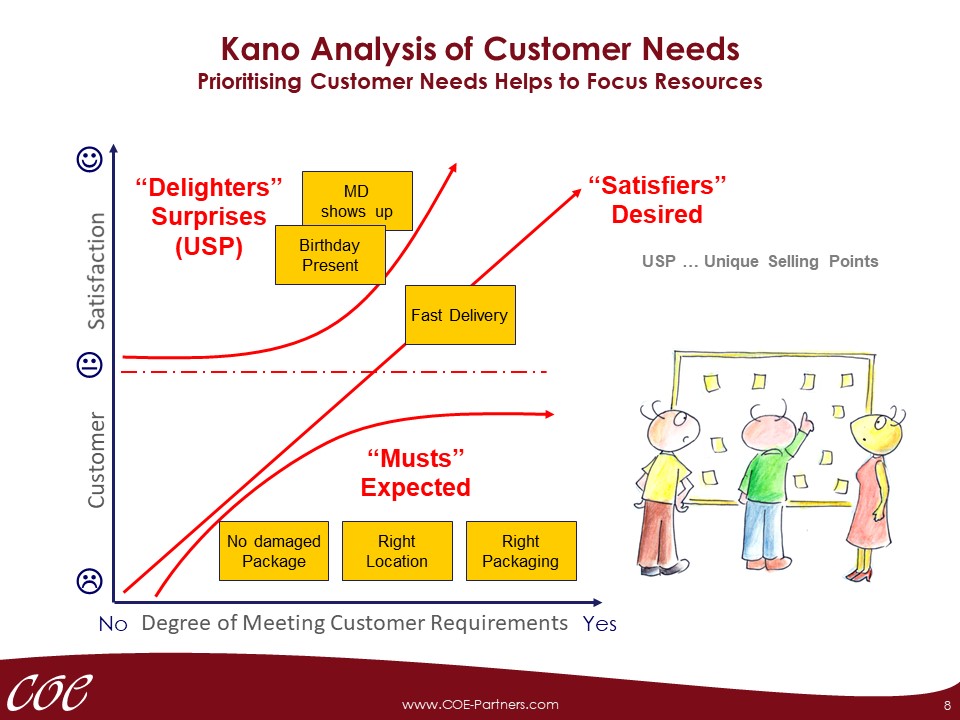

The Kano diagramme is a qualitative tool that helps prioritising customer requirements. This diagramme shows the relationship of customer satisfaction to degree of meeting customer requirements. Customer requirements appear in three categories: musts, satisfiers and delighters (Figure 7).

Musts are customer needs that always need to be met because customers assume they are provided, often without mentioning them. If these characteristics are not offered, customers will certainly be dissatisfied. However, offering these characteristics does not mean customers are satisfied. They may not even recognise that these characteristics are offered. For example, a bank has to have ATMs. Having an ATM does not lead to customer satisfaction, but customers would not understand if a bank does not offer ATM services, hence not having an ATM certainly raises complaints by customers.

Satisfiers, or the more the better characteristics, are customer needs with a near linear effect on customer satisfaction. Not offering satisfiers will lead to customer dissatisfaction. Offering satisfiers to a certain degree leads to a certain level of satisfaction. Offering satisfiers to a very high degree may lead to delighted customers. For example, long waiting time at banking counters leads to dissatisfaction, whereas some minutes would be acceptable. If the waiting time is closed to zero continuously, the customer would be satisfied or even positively surprised.

Delighters are usually not required by the customers. Very often, customers do not even know of these characteristics. Offering delighters may delight customers in a very positive way so that these may stand as the unique selling point of the offerings and make the difference to the competition for a certain period of time. Delighters are used to attract new customers and win them out of the hands of competitors.

For example, it would be a nice surprise if the customer would be offered a coffee when entering a bank – until the customer gets used to it or/and all banks offer this service.

Customer requirements change over time so that delighters become satisfiers and turn into musts over a long enough period.

For instance, a bank could score with online banking some twenty years ago. Nowadays, this option is an absolute must for each bank and each account type.

Prioritising customer requirements is a necessity before scope, metrics and targets of the project can be finalised. For each improvement project two factors should be considered: the priority of metrics in scope and the actual degree of meeting their targets.After identifying customer requirements and translating them into process metrics, their specifications, i.e. their targets have to be set. These targets can be determined in different ways.

In a business to business relationship, so called service level agreements (SLA) are negotiated. These SLA determine requirements of customers and characteristics offered by vendors of products and services in a contract.

By way of example, the driver “frequent sales calls” could be specified in an SLA as “One visit per month” and “one call per week”. These indicators are measurable and their fulfilment can be checked.

In the relationship with end consumers, there are no SLAs. However, meeting and exceeding customer expectations is just as important in order to retain customers and win over new ones. Therefore, it is essential to know what competitors offer and hence what target would be appropriate to satisfy or even delight customers.

For driver “easy to apply” in the metrics is “time to complete application form”. Comparing the application form with those of competitors is easy to do. Translating complexity and understand ability of the form into process indicators is not straight forward. A proxy measure would be the time needed to fill in the form by a non-banking person, a typical customer. The result is “Must be able to do it in less than two minutes”.

The capability of the process to meet this target does not influence target setting at any point in time. Targets are set by process customers.

Conclusion – Lean Six Sigma DEFINE Phase

After the Lean Six Sigma DEFINE phase has been completed by undergoing the above mentioned tasks, the Lean Six Sigma phase

This Lean Six Sigma DEFINE phase has the following deliverables:

- A project charter

- A prioritised list of customer requirements translated into specifications

- A high-level process map

- A stakeholder catalogue examining the support of key personnel for the project and measures to mobilise additional resources and backing if necessary.